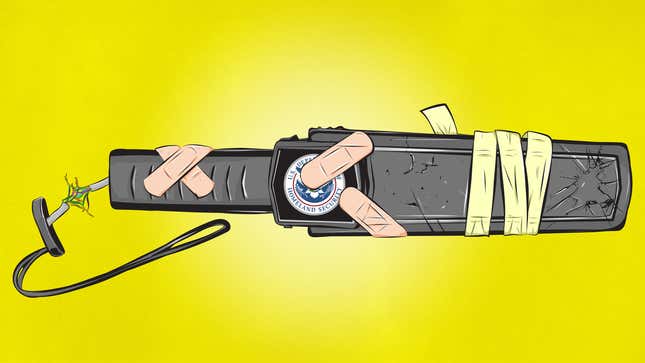

We have this macabre ballet we do in the airport. We stand in agonizingly long lines, winding around stanchions as our boarding times tick ever closer. It’s a routine borne of tragedies that could hypothetically happen, and we have cast the Transportation Security Administration as our stage directors. Airports are miserable not because the TSA is especially incompetent, but because we demanded security theater, and we wouldn’t have it any other way.

The TSA, born after the September 11th attacks and nestled within cozy confines of the Department of Homeland Security, is one of many American autoimmune reactions to the worst terrorist attack perpetrated against the United States. Because the attackers used planes, America wanted to make sure that planes were safe, and the best way to do that was to make sure that only the right people got on them.

The Big Haystack

The TSA’s mandate, from the Aviation and Transportation Security Act passed in the fall of 2001, requires that it “oversee the screening of passengers and property” at airports.

The TSA’s job, from the outset, is to sift through a haystack containing every passenger and every piece of luggage they’ve brought with them, and make sure no dangerous person or harmful weapon gets through. Here is the scale of that haystack: In 2015, airlines flying to and within the United States carried a total of 895,500,000 passengers. Of those, the TSA says they screened 708,316,339 passengers, and accompanying those passengers 1.6 billion carry-on bags and 432 million checked bags.

The haystack is gargantuan. And the TSA would really, really prefer if it were smaller, especially for passengers hurrying to get through security and sprint down the terminal to catch their flight. To thin that category, the TSA exempts some people from screening. Some of this is by age: children 12 and younger and adults 75 and older don’t have to go through the same strict scrutiny as everyone else. Another way is by incorporating screening already done: government employees with security clearances and members of the military the TSA can count as pre-screened, and then just send them through shorter lines.

But for the rest of us, the TSA has to get us to opt-in, and that means pre-check, where people pay $85, submit documentation, and go to a special screening for the TSA to remove them from the baseline category of possibly a risk. In exchange, if they get approval, they get five years of shorter lines and easier flight.

Or at least they would, if Congress funded the TSA enough to keep pre-check lanes open. Congress doesn’t, instead regularly cutting funding. The House of Representatives voted to cut TSA funding in 2011. Sequestration cut TSA funding in 2013.

In 2014, Congress passed a TSA fare increase, and used the overwhelming majority of that not to fund the TSA, but to pay down the national debt. When the TSA fare went up in 2014 (as did the prices of tickets it was attached to), Congressional funding cuts to the TSA meant the TSA cut 3,500 screener positions. And in 2015, the House voted to increase TSA funding, but cut TSA employee pay. The TSA may have been conceived as a vital layer of national security, but nothing about its funding reflects that.

Lunging At Shadows

Without enough pre-screened people to rush through the special express lanes, what’s the TSA to do? Pick people out of the crowd and hope they’re fine. From the Wall Street Journal:

TSA doesn’t have enough screeners to reserve PreCheck lanes only for PreCheck passengers. So the agency directs passengers considered low risk, often based on age, sex and destination, into PreCheck lanes, hoping that a taste of expedited screening will prompt them to pay the $85 application fee to enroll for five years.

There’s a lot of subjective judgement that goes into just who in line looks safe enough for a screener to send along, and none of it looks good. The risk of terrorist attacks is fortunately astoundingly rare, so letting passengers through lightly screened doesn’t really change that, but cavalier and arbitrary filtering of passengers factors plays a big part in the TSA’s other big security check: the No-Fly List.

The No-Fly List is a government compiled secret registry of people who are deemed too dangerous to let on airplanes. The No-Fly List has been abused by individuals and government, and sometimes it catches 8-year-olds instead of suspected terrorists. While the No-Fly List system has some gradients of risk, it’s a blunt measure, and one so opaque it’s impossible to know how accurate and useful it is. It also assumes that people dangerous enough to be on the list are also likely to fly under their real names, which is a dubious assumption.

Instead of screening by identity, other countries check passengers by behavior. Israel’s Ben-Gurion airport is renowned for its security, which is based on profiling that’s a combination of behavioral and racial (the latter of which is rightfully officially prohibited by the TSA, though allegations of racial profiling against it continue). As the Washington Post noted in 2010:

Israel’s approach allows most travelers to pass through airport security with relative ease. But Israeli personnel do single out small numbers of passengers for extensive searches and screening, based on profiling methods that have so far been rejected in the United States, subjecting Arabs and, in some cases, other foreign nationals to an extensive screening that comes with a steep civil liberties price.

The TSA began its own behavior screening program behavior, called “Screening of Passengers by Observation Techniques,” or “SPOT,” in 2007. Many of the screening criteria were absurd, and easily applied to stressed passengers worried they’ll miss their flight. Which makes sense, because according to the government itself, the behavioral screening relied on bunk science.

“Congress should consider the absence of scientifically validated evidence for using behavioral indicators to identify threats to aviation security when assessing the potential benefits and cost in making future funding decisions for aviation security,” a 2013 report by the Government Accountability Office evaluated the program and concluded. There’s also the basic fact that once profiles are figured out, a determined terrorist organization could adapt its behavior to again avoid detection.

And there’s a good chance such screening violates the constitution. In 2015, the ACLU sued the TSA over the program.

Weighed Down With Extra Baggage

Besides passengers, the TSA is also screening 1.6 billion carry-on bags and 432 million checked bags. If the TSA could check those safely and simply, then that might shorten the interminable lines while protecting travelers from threatens hidden in suitcases.

The TSA’s Instagram account is filled with pictures of objects they’ve screened out, most often guns, knives, and, around July, fireworks. These objects can only really be screened in airports, and despite social media boasts, the TSA’s fail rate last summer was an appalling 95%.

Why? Partly, because tests skip past other layers of security. Another reason is that it’s much easier for the TSA to screen checked bags than carry-ons, and airlines keep discouraging people from checking bags. In 2014, airlines made $1 billion from checked bag fees, even with three-fourths of bags carried on. And those carry-ons are much harder to scan.

Checked bag fees were introduced in the early 2000s and became almost industry-wide by 2008, in part as a way for struggling airlines to maintain revenue. (Or maybe, because bag fees for the airlines are tax-exempt, it’s a weird tax arbitrage strategy). Their persistence, combined with travelers bringing more and more of their belongings as carry-on, has led to calls for both an end to bag fees and an end to carry-ons altogether.

But Is It Even Necessary?

Ultimately, the TSA’s airport screening exists as the second-to-last line of defense for a threat that is astoundingly rare. In 2015, there was one major terrorist attack on an airliner, and it was a Russian plane in Egypt. Airline attacks were never common to being with, and in as much as there’s an annual rate of terrorism, it’s down. It’d be easy for intelligence agencies to claim credit, and they certainly claim some with plots foiled overseas, but mostly, it’s that outcomes for terrorists are worse beyond security. The actual last line of defense is, according to security researcher Bruce Schneier, “the reinforcement of cockpit doors, and the fact that passengers know now to resist hijackers.” These changes, more than anything else, are what keep Al Qaeda copycats from turning other airliners into building-bound missiles.

And those changes don’t require us to get to the airport three hours early, cram all of our belongings into overstuffed carry-on bags, remove our shoes, risk further screening for appearing nervous, or subject ourselves to background checks in advance. Instead, we created the TSA, tasked it with a massive task, and hobbled it with bad science, weak funding, contradictory mandates, and a general lack of support, so that we can have the illusion of security in the form of inconvenience.

Kelsey D. Atherton is a defense journalist. His work regularly appears at Popular Science, and he edits even nerdier stories at Grand Blog Tarkin. He is as interested in the future of war as he is uninterested in actually calling them UAVs, not drones.